DH Research

Real and imaginary colonial geography

How do imperial imagination—culture, symbols, art, language, tropes—and imperial reality—conquest, territory, enslavement, exploitation—shape each other? In particular, how do the geographies imagined in colonial texts relate to concrete colonial maneuvers?

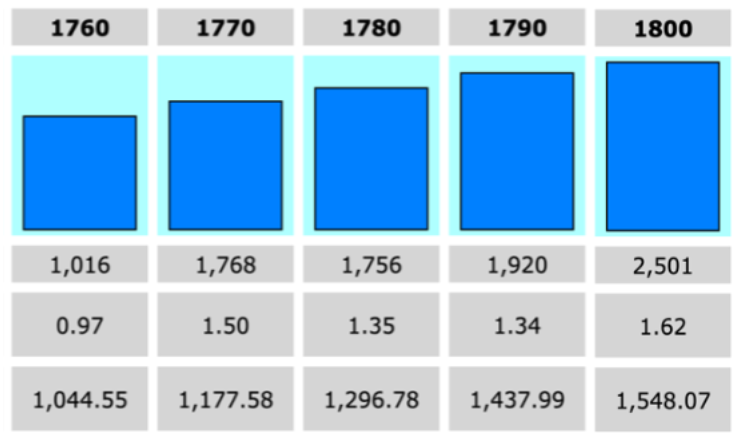

To approach these general questions, I conducted a computational analysis on the relationship between the geographies of eighteenth-century British maritime literature and ship itineraries. Specifically, I trained a custom named entity recognition (NER) model to find and count place names in a mid-size corpus of texts, then compared those results to archives of voyages by Royal Navy, British East India Company, and slave trading vessels. I cast colonial place names as navigational technologies akin to the logbook, the ledger, and the geographic information system (GIS), offering that by turning the methods of imperial geography back on itself, we can better dissect their continuing functioning in order to counter them. Specifically, in addition to findings on English nationalism, fungibility in Africa and China, and the imaginary bypassing of environmental constraints, I find that imaginary geographies anticipate real colonial conquest. I affirm Edward Said’s argument: “The slow and often bitterly disputed recovery of geographical territory which is at the heart of decolonization is preceded—as empire had been—by the charting of cultural territory.”

The first phase of this project is forthcoming in PMLA. I also designed an interactive Shiny app to map the places mentioned in texts alongside ship itineraries. The project also informed a forthcoming chapter, “Mapping Empire’s Horror: Literary GIS and Colonial Spatial Logic” in Space and Literary Studies, edited by Elizabeth Evans for Cambridge University Press. There, I argue that “literary GIS,” the subfield of the digital humanities that uses geographic information systems (GIS) to make digital maps of texts, is useful insofar as it can help us see colonial spatial logic–largely because it depends on such logic–but that such vision does not necessarily help articulate alternatives to empire. Future work on this project will revise the methods for detecting place names, consider non-toponymic geographies, and compare the findings to later anti-colonial and colonial writing from the United States.

Voice

Collaborators: Nika Mavrody; Laura McGrath; Nichole Nomura

At the Literary Lab, we investigated the contemporary semantics of “voice,” a literary critical concept prized across the literary field by academics, reviewers, authors, agents, and readers. Examining thousands of reviews from Goodreads and periodicals, blurbs, and author interviews in The Paris Review, plus close readings of selected novels, we argue that all these critical discourses agree that voice is what mediates between texts’ internal form and paratextual framing, most markedly between the narrator’s viewpoint and the author’s identity. In particular, we use vector space models of reviews to pinpoint the relations among voice, style, and genre, finding that “Style - Genre = Voice”: voice is the individual, non-generic kernel within style. We (published) our findings in a joint issue of Cultural Analytics and Post45.

Modeling domestic space

Collaborators: Mark Algee-Hewitt; Julia Gershon; Svenja Guhr; Annie Lamar; Jessica Monaco; Sarah Sophie Schwarzhappel; Matt Warner

In an ongoing project at the Literary Lab, we are attempting to model the occurrence of domestic settings in nineteenth-century British fiction. One impetus for the project is attempting to stretch computational literary geography beyond a focus on place names. Domestic space, we hypothesize, is an appealing case because of the “technology” of domestic terminology: room names, furniture, domestic activities, and so on.

We are currently annotating texts to train a variety of models, including large language models. Questions include: Is it possible to model whether a passage is taking place in a house versus a ship, castle, or nowhere in particular? To what extent? What are the textual features that mark domestic space? Are novels with a lot (or a little) domestic space also unique in other ways, e.g., in their representations of gender and race, prevalence of dialogue, or use of place names? Do overall proportions of domestic space in novels change over the course of the century?

Scientific passive voice

I am in the early stages of a project on 48,000 scientific articles from the Royal Society Corpus that studies their usage of the passive voice. Building on similar questions motivating my dissertation’s close readings of the virtual position–one plank of which is the passive voice–this project asks where, when, how, and why the passive voice specifically became so prevalent in science writing. Early findings suggest that the late eighteenth century was a decisive period. Possible hypotheses include that the passive voice correlated with topics related to navigation at sea; the precursors of what would become colonial anthropology; and the institutionalization of science under state agencies.